keywords: COVID-19 testing optimization, Pool testing mathematics, Pandemic response strategies, Test positivity rates, Binomial distribution in epidemiology

To control the COVID-19 pandemic requires rapid testing of many people. One way to do this is to perform a single test on the combined samples taken from a group of people, called pool testing. The American Society for Microbiology thinks it's time to jump in the pool and STAT agrees.

How Pool Testing Works¶

Here's an example of how pool testing works. Suppose the test requires a drawn blood sample. If the combined sample from a group of people comes back negative then with one test we've eliminated everyone in the group from further testing. In cases where a large fraction of the population remains susceptible, this can reduce the number of tests needed.

On the other hand, if the test is positive then we know at least one of the people in the test pool has been infected. In that case, we'll need to run a second test.

Suppose we assign 50 people in each pool. It would be efficient to split the original 50 into something like five groups of 10 people and to do pool testing again on each of these smaller pools. But then you'd have to either get everyone from the original group back to take more blood samples (and who wants that?), or you'd have to use partial samples at each step and keep track of who was in each subset of the original.

Instead, consider splitting everyone's sample into two - one pooled and one retained for retesting if the pool is positive. If the pool test indicates the presence of COVID-19 then we'll run a retest on the second half sample for everyone in the pool. The CDC recommends this procedure,

"If a pooled test result is negative, then all specimens can be presumed negative with the single test. If the test result is positive or indeterminate, then all the specimens in the pool need to be retested individually. The advantages of this two-stage specimen pooling strategy include preserving testing reagents and resources, reducing the amount of time required to test large numbers of specimens, and lowering the overall cost of testing."

But how do you decide how many people to include in each pool? If you make the sample size too large then you increase the chance one or more of them is infected and you have to go back and test them all again anyway. If you make the pools too small then you might be running more tests than necessary.

Even worse, until you start testing you don't know what fraction of the population is infected so you might over or under estimate the background rate. How deep should you make the pool?

Pool Probabilities¶

Let's say you want to test a population of N N N people using pool sizes of n n n people (the depth of the pool) where the probability of being infected is p p p. You'll begin by forming P = N / n P = N/n P=N/n pools (with some rounding if n n n doesn't go into N N N evenly). Of those, some fraction α ( 0 ≤ α ≤ 1 ) \alpha \; (0 \leq \alpha \leq 1) α(0≤α≤1) of them will be positive. Again, ignoring rounding α P \alpha P αP pools will be positive, so you'll need to retest α P n \alpha P n αPn individual samples. In other words, the total number of tests run will be P + α P n P + \alpha P n P+αPn. What is the optimal value for n n n as a function of P P P and p p p?

What we need to do is to find the minimum of the function T ( n , p ) T(n,p) T(n,p) where T T T represents the number of required tests,

T ( n , p ) = P + α P n = P ( 1 + α n ) = N ( 1 n + α ) T(n,p) = P + \alpha P n = P (1 + \alpha n) = N \left( \frac{1}{n} + \alpha \right) T(n,p)=P+αPn=P(1+αn)=N(n1+α)where α \alpha α will be a function of the probability of a positive test. This is a Binomial distribution,

α ( k , n , p ) = P r ( k ; n , p ) = ( n k ) p k ( 1 − p ) n − k \alpha(k,n,p) = Pr(k;n,p) = \binom{n}{k} p^k (1 - p)^{n-k} α(k,n,p)=Pr(k;n,p)=(kn)pk(1−p)n−kfor k = 0 , 1 , … , n k = 0,1, \ldots, n k=0,1,…,n which gives the probability of k k k failures in n n n tests when the probability of failure (infection) for a single individual is p p p.

For our case, all we're concerned about is the case k = 0 k = 0 k=0, P r ( 0 ; n , p ) = ( 1 − p ) n Pr(0;n,p) = (1-p)^n Pr(0;n,p)=(1−p)n when the test returns a negative result since 1 − p 1-p 1−p is the probability someone is not infected and ( 1 − p ) n (1-p)^n (1−p)n means all n n n people in the pool test negative.

The test function T T T is then

T ( n , p ) = N n ( 1 + ( 1 − ( 1 − p ) n ) n ) T(n,p) = \frac{N}{n} \left( 1 + ( 1 - (1-p)^n ) n \right) T(n,p)=nN(1+(1−(1−p)n)n)or

T ( n , p ) = N ( 1 n + 1 − ( 1 − p ) n ) . T(n,p) = N \left( \frac{1}{n} + 1 - (1-p)^n \right). T(n,p)=N(n1+1−(1−p)n).To recap, the term 1 − ( 1 − p ) n 1 - (1-p)^n 1−(1−p)n comes from the fact that each person has a probability p p p of being infected or 1 − p 1-p 1−p of being virus-free. We're assuming everyone's chances of being infected are independent of everyone else, so the probability that all n n n people in the pool are not infected is the product ( 1 − p ) (1-p) (1−p) n n n times, which gives ( 1 − p ) n (1-p)^n (1−p)n. But if one or more are infected then the test for that pool will fail, which is the complement, or 1 − ( 1 − p ) n 1 - (1-p)^n 1−(1−p)n.

Of course, people don't become infected independently of everyone else, but for this example, we'll assume independence. We're also assuming the tests are perfect, which they aren't. This can make a big difference to the estimate of infection rate.

Suppose the test is 97% accurate, which seems pretty good. This means that if a person is infected the test will almost always be correct, and out of 100 tests, it will be wrong about 3 times. If the true infection rate is 1%, then out of 100 people only 1 will actually be infected and the test will likely correctly determine this. Of the remaining 99 people though, it will incorrectly say about 3 of them are infected when in fact, they are not.

So now it appears that 4 out of 100 or 4% are infected. Since we need to know the probability of infection p p p correctly to be able to set the depth of the pool n n n, in this case, we'd be off by 400%. Even worse, the accuracy of tests tends to decrease as the pool size increases. For this analysis though, we'll assume a perfect test.

To find the number of tests required for a given infection rate p p p means we need to find the value of n n n that makes T ( n , p ) T(n,p) T(n,p) the smallest.

Optimum Pool Sizes¶

A little calculus here—we need to find

d T ( n , p ) d n = − ( 1 − p ) n log ( 1 − p ) − 1 n 2 = 0 \frac{dT(n,p)}{dn} = -(1-p)^n \log(1-p) - \frac{1}{n^2} = 0 dndT(n,p)=−(1−p)nlog(1−p)−n21=0for some value of n n n. That is, we're looking for the point on the curve where the slope is zero which will indicate either a minimum, a maximum, or an inflection point. Without going into any more, it turns out these points are the minimum values we're looking for.

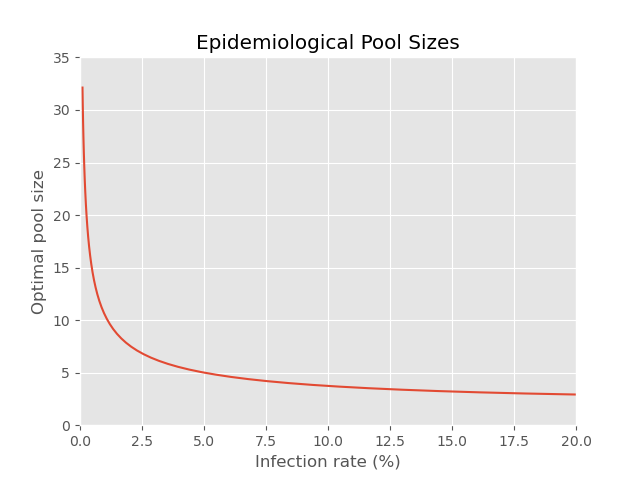

Solving d T d n = 0 \frac{dT}{dn} = 0 dndT=0 for various values of p p p gives this plot: (python code here)

shows that for infection rates above about 1% the pool sizes are less than 10 people, and by the time the positivity is above 5% the pool size needs to drop to 5 people or fewer.

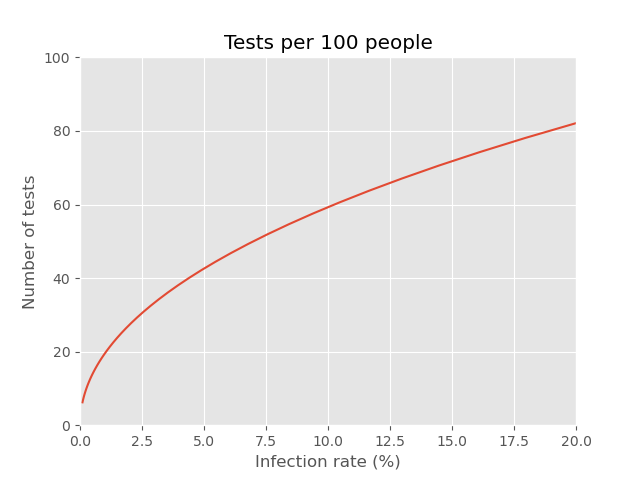

Once we have the optimal number of people per pool then for each infection probability p p p we can calculate the number of required tests T ( n , p ) T(n,p) T(n,p) shown here:

If you'd like a review of derivatives Grant Sanderson's "Derivative formulas through geometry" video is a very good start and is part of his The Essence of Calculus series. A complete calculus course is also available from Khan Academy's Calculus I.

The Need for More Testing¶

Johns Hopkins University has been tracking COVID-19 cases and testing which shows the current positivity rate for the U.S. is about 7.5% (as of August 7th), and there's also a state-by-state breakdown which shows the positivity rates running from -4.6% to 20.9%. The negative positivity rate (does that even make sense?) is a result of how the scoring is done and the fact that reporting isn't fully available for all states. But what this shows is for a 7.5% positivity rate, the optimal pool size is around 4 and we'll need 50 tests for every 100 people. So, sure we'll save half the number of tests, but it's not a big reduction. By the time the background rate is 20%, it's hardly worth bothering with pool testing.

But here's a thought that might seem a bit counter-intuitive at first. The problem is we aren't testing enough. The reason the positivity rates are so high is that there's self-selection bias happening.

People ask to be tested because they don't feel well or think they may have been exposed. Many of them are infected which drives the positivity rates up. If we could get to the point where much of the general population is being tested, then most of the people being tested wouldn't be infected and it would make more sense to do pool testing.

This shows that to make COVID-19 pool testing worthwhile the test will need to be very accurate and we'll need to test a lot of people even if they have no reason to think that they may be sick or have been exposed.

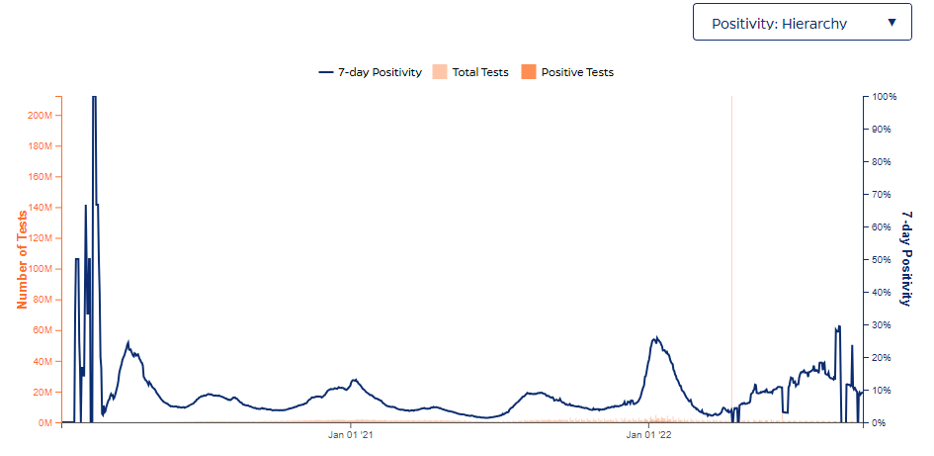

The CDC stopped collecting test data on September 21, 2022. The description of the final plot says,

This graph shows the total daily number of virus tests conducted in each state and of those tests, how many were positive each day. The trend line in blue shows the average percentage of tests that were positive over the last 7 days. The rate of positivity is an important indicator because it can provide insights into whether a community is conducting enough testing to find cases.

Usama Kadri from Cardiff University has developed a linear algebra method that tests samples from the same person in different pools multiple times to identify infected people, but it requires automated testing methods that may not be available to many hospitals. You can read about his technique in the 7 Oct 2020 edition of SciTechDaily.

Image credits¶

Hero: peterschreiber.media / Shutterstock

Daily state-by-state testing trends chart: Johns Hopkins

Code for this article¶

optPoolSize.py - Estimates the optimal pandemic testing pool size.