keywords: Prison Mathematics Project, Pell's equation, Chakravala method, Christopher Havens, mathematical rehabilitation

I have never done anything "useful". No discovery of mine has made, or is likely to make, directly or indirectly, for good or ill, the least difference to the amenity of the world.

— G. H. Hardy

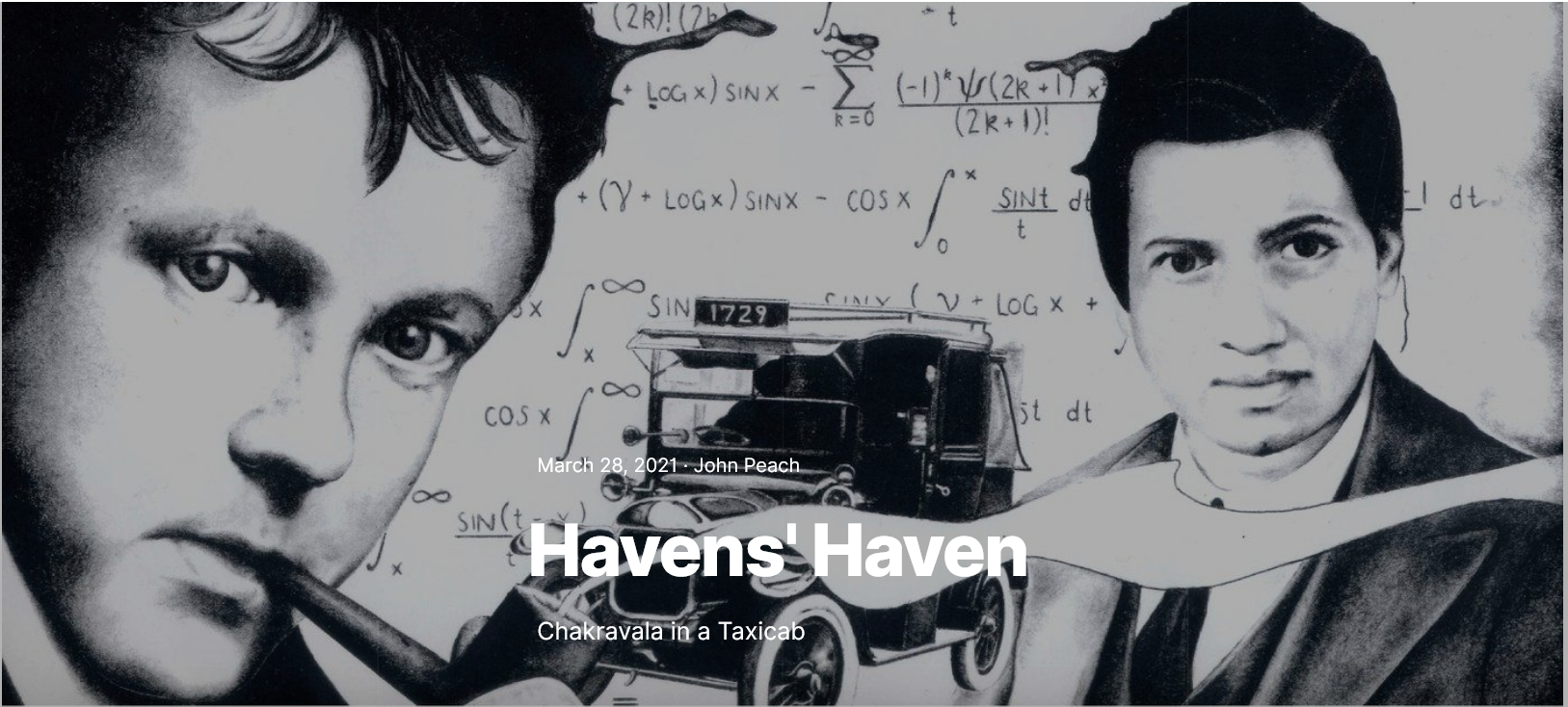

Christopher Havens¶

If you were facing a 25 year stretch for murder and had landed in solitary for a while, you might think to yourself, "Maybe this would be a good time to catch up on some number theory". Something like this occurred to Christopher Havens when he was convicted of murdering Randen Robinson and sent to the Washington State Monroe Correctional Complex northeast of Seattle. He had dropped out of high school, began using drugs, and killed Robinson during a drug-related dispute. After his conviction, bad behavior sent him to solitary confinement for a year.

While in solitary, Havens started working puzzles and then realized that the guards were handing out math problems to other prisoners. He did as much math as they could provide, quickly learning calculus and number theory, but eventually exceeded the guards' ability to keep up with his level.

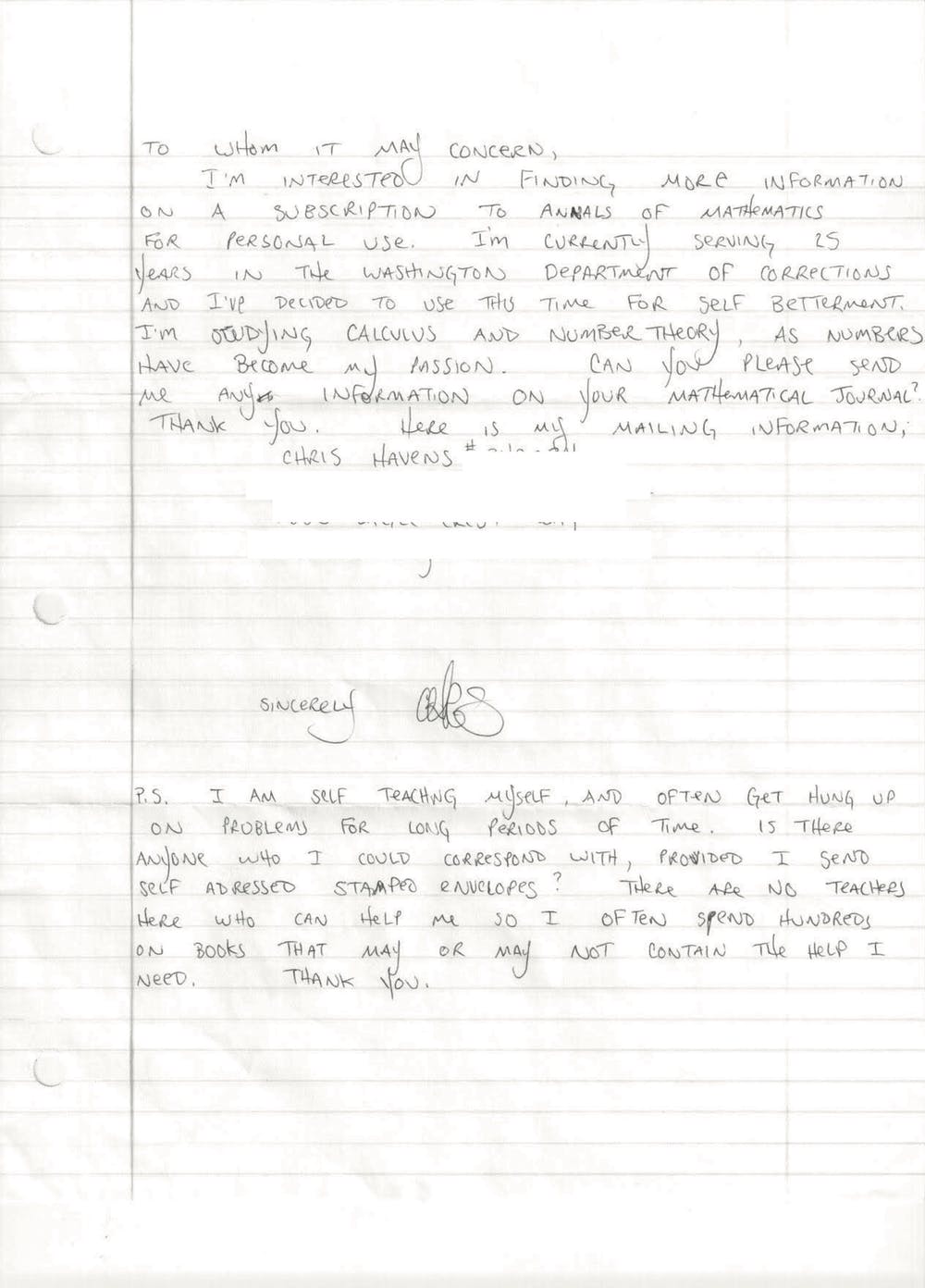

That's when he sent this letter that eventually arrived on the desk of Matthew Cargo, editor for Mathematical Sciences Publishers, whose partner Marta Cerruti is Associate Professor of Materials Engineering at McGill University.

Her parents are mathematicians and her father, Umberto Cerruti, is a number theorist at the University of Torino in Italy. Umberto Cerruti sent Havens a problem to work on, and Christopher wrote back with a long, complicated solution that turned out to be correct.

Christopher has since published a paper jointly with Cerruti and two other mathematicians, in the journal Research in Number Theory, "Linear fractional transformations and nonlinear leaping convergents of some continued fractions". He hopes to inspire other prisoners through mathematics and has started the Prison Mathematics Project (PMP) to connect inmates with mathematicians. They hold bi-weekly meetings to discuss math problems and work on larger projects. Beginning in 2016 the PMP has been holding Pi Day celebrations.

"You should never set aside your dreams and goals and dismiss them as impossible just because you are institutionally challenged," Havens said. "Today is not just a day to celebrate pi, but mathematics as a whole and celebrate an opportunity we have to move our lives in a positive direction."

Besides having a research paper published, Chris also submitted a problem to Math Horizons, a magazine published by the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) meant to be accessible to undergraduate mathematics majors. The problem is this, What is the smallest positive integer y y y such that 1729 y 2 + 1 1729y^2 + 1 1729y2+1 is a perfect square? This is a form of Pell's Equation, and there's a connection to the mathematicians Srinivasa Ramanujan and G. H. Hardy.

Ramanujan was a self-taught mathematician from India who produced thousands of new ideas in number theory. In early January 1913, he sent a letter with some of his results to Hardy who was at Cambridge at the time. Later, Hardy said that the letters were "certainly the most remarkable I have received" and that Ramanujan was "a mathematician of the highest quality, a man of altogether exceptional originality and power". He invited Ramanujan to visit him in England, and Ramanujan arrived in April 1914.

Ramanujan (22 December 1887 - 26 April 1920) was ill most of his short life and Hardy visited him while he was in the hospital.

1729 = 1 3 + 1 2 3 = 9 3 + 1 0 3 1729 = 1^3 + 12^3 = 9^3 + 10^3 1729=13+123=93+103I remember once going to see him when he was ill at Putney. I had ridden in taxi cab number 1729 and remarked that the number seemed to me rather a dull one, and that I hoped it was not an unfavourable omen. "No," he replied, "it is a very interesting number; it is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways."

The number 1729 1729 1729 is now known as a taxicab number or the Ramanujan-Hardy number and is the number Havens chose for the problem. The drawing at the top of Hardy and Ramanujan was done by Chris Havens.

Pell's Equations¶

Pell's equations are in the form

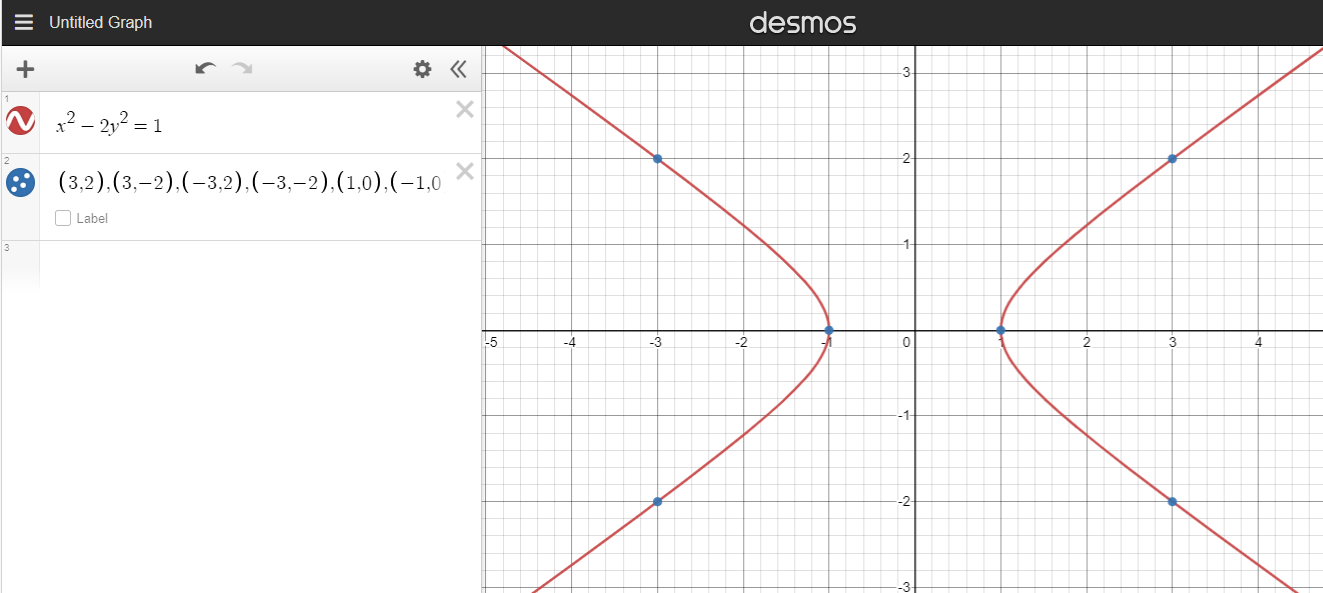

x 2 − n y 2 = 1 x^2 - ny^2 = 1 x2−ny2=1for integers x , y x,y x,y, and n n n. The problem that Chris Havens proposed is to find x x x and y y y such that x 2 = 1729 y 2 + 1 x^2 = 1729y^2 + 1 x2=1729y2+1, which can be rearranged into a Pell equation,

x 2 − 1729 y 2 = 1. x^2 - 1729y^2 = 1. x2−1729y2=1.In the 7th century, Indian mathematician and astronomer Brahmagupta first studied equations in this form (he called it the Varga-Prakriti equation), and Pell had nothing to do with them. This is an example of Stigler's Law of Eponymy, named for University of Chicago statistics professor Stephen Stigler, which says that no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer. Stigler's Law is itself an example, having been earlier described by sociologist Robert K. Merton. Leonard Euler misattributed the equations to Pell rather than to the several earlier mathematicians who worked on similar equations including Diophantus, Bhāskara II, Narayaṇa Paṇḍita, William Brouncker, and Pierre de Fermat.

The equations are hyperbolic functions and have solutions at points where both x x x and y y y are integers. This is an example of the equation x 2 − 2 y 2 = 1 x^2 - 2y^2 = 1 x2−2y2=1 plotted in Desmos. Use "x^2-2y^2=1" to plot the function, and plot solutions in the form ( x , y ) (x,y) (x,y) as shown on the second line.

In the 12th century, Bhāskara II II, also known as Bhaskara or as,quantities, including the length of the sidereal year.) (1114–1185) continued the work of Brahmagupta (598–670) and developed an algorithm for finding solutions that he called the Chakravala Method.

The Chakravala¶

Bhāskara named his method Chakra (meaning "wheel") because of its iterative nature. Shailesh Shirali is a mathematician at the Sahyadri School in India who wrote "The Chakravala Method - Zeroing in on a Solution" in the mathematics journal At Right Angles. This description of the Chakravala is from his paper.

The first step to understanding the Chakravala comes from the Diophantus-Brahmagupta-Fibonacci identity,

( a 2 + b 2 ) ( c 2 + d 2 ) = ( a d − b c ) 2 + ( a c + b d ) 2 = ( a d + b c ) 2 + ( a c − b d ) 2 . \begin{align} (a^2+b^2)(c^2+d^2) &= (ad-bc)^2 + (ac+bd)^2 \\ &= (ad+bc)^2 + (ac-bd)^2. \end{align} (a2+b2)(c2+d2)=(ad−bc)2+(ac+bd)2=(ad+bc)2+(ac−bd)2.Brahmagupta extended this to

( a 2 − n b 2 ) ( c 2 − n d 2 ) = ( a c + n b d ) 2 − n ( a d + b c ) 2 = ( a c − n b d ) 2 − n ( a d − n b c ) 2 . \begin{align} (a^2-nb^2)(c^2-nd^2) &= (ac+nbd)^2 - n(ad+bc)^2 \\ &= (ac - nbd)^2 - n(ad-nbc)^2. \end{align} (a2−nb2)(c2−nd2)=(ac+nbd)2−n(ad+bc)2=(ac−nbd)2−n(ad−nbc)2.It's not clear how these identities were discovered, but they are easy to verify by expanding and collecting terms. You can start to see how the Chakravala works for finding integer solutions to the equation x 2 − n y 2 = k x^2-ny^2 = k x2−ny2=k if we already have two solutions,

a 2 − n b 2 = k 1 c 2 − n d 2 = k 2 \begin{align} a^2-nb^2 = k_1 \\ c^2-nd^2 = k_2 \end{align} a2−nb2=k1c2−nd2=k2then

( a c + n b d ) 2 − n ( a d + b c ) 2 = k 1 k 2 . (ac+nbd)^2 - n(ad+bc)^2 = k_1k_2. (ac+nbd)2−n(ad+bc)2=k1k2.To complete the method, we need Bhāskarā’s lemma which says that if a 2 − n b 2 = k a^2-nb^2 = k a2−nb2=k, then

( m a + n b k ) 2 − n ( a + b m k ) 2 = m 2 − n k , \left( \frac{ma+nb}{k} \right)^2 - n \left( \frac{a+bm}{k} \right)^2 = \frac{m^2-n}{k}, (kma+nb)2−n(ka+bm)2=km2−n,which can be easily verified with expansion and collection of terms.

Given a non-square positive integer n n n, we're looking for a solution to x 2 − n y 2 = k x^2 - ny^2 = k x2−ny2=k. If we have two solutions [ a , b , k 1 ] [a,b,k_1] [a,b,k1] and [ c , d , k 2 ] [c,d,k_2] [c,d,k2] a third solution [ u , v , k 1 × k 2 ] [u,v,k_1 \times k_2] [u,v,k1×k2] can be generated from the Brahmagupta identity using

u = a c + n b d v = a d + b c . \begin{align} u &= ac + nbd \\ v &= ad + bc. \end{align} uv=ac+nbd=ad+bc.Suppose n = 10 n=10 n=10 and we have two solutions [ 7 , 2 , 9 ] [7,2,9] [7,2,9] and [ 11 , 3 , 31 ] [11,3,31] [11,3,31] meaning that

7 2 − 10 × 2 2 = 9 and 1 1 2 − 10 × 3 2 = 31. 7^2-10 \times 2^2 = 9 \text{ and } 11^2 - 10 \times 3^2 = 31. 72−10×22=9 and 112−10×32=31.Using the equations for u u u and v v v,

u = 7 × 11 + 10 ( 2 × 3 ) = 77 + 60 = 137 v = 7 × 3 + 2 × 11 = 21 + 22 = 43 , \begin{align} u &= 7 \times 11 + 10(2 \times 3) = 77 + 60 = 137 \\ v &= 7 \times 3 + 2 \times 11 = 21 + 22 = 43, \end{align} uv=7×11+10(2×3)=77+60=137=7×3+2×11=21+22=43,gives a new solution [ 137 , 43 , 9 × 31 ] = [ 137 , 43 , 279 ] [137,43,9 \times 31] = [137,43,279] [137,43,9×31]=[137,43,279],

13 7 2 − 10 × 4 3 2 = 18769 − 18490 = 279. 137^2 - 10 \times 43^2 = 18769 - 18490 = 279. 1372−10×432=18769−18490=279.If we already have one triple [ a , b , k 1 ] [a,b,k_1] [a,b,k1] that works, a second one can be derived by using ( m ) 2 − n × 1 2 = m 2 − n (m)^2 - n \times 1^2 = m^2-n (m)2−n×12=m2−n giving the triple [ c , d , k 2 ] = [ m , 1 , m 2 − n ] [c,d,k_2] =[m,1,m^2-n] [c,d,k2]=[m,1,m2−n] and calculating a new u u u and v v v,

u = m a + n b v = a + b m \begin{align} u &= ma + nb \\ v &= a + bm \end{align} uv=ma+nb=a+bmso

u 2 − n v 2 = ( m a + n b ) 2 − n ( a + b m ) 2 = k 1 ( m 2 − n ) . u^2 - nv^2 = (ma+nb)^2 - n(a+bm)^2 = k_1(m^2 - n). u2−nv2=(ma+nb)2−n(a+bm)2=k1(m2−n).The trick to finding a solution for x 2 − n y 2 = 1 x^2 - ny^2 = 1 x2−ny2=1 is to start with an "almost" solution and iterate using the Chakravala until k ( m 2 − n ) = 1 k(m^2-n) = 1 k(m2−n)=1. Finding [ a , b , k 1 ] [a,b,k_1] [a,b,k1] is done by letting b = 1 b=1 b=1 and then setting a a a to the nearest integer greater than n \sqrt{n} n so that a 2 − n = k 1 a^2 - n = k_1 a2−n=k1 gives the smallest positive integer k 1 k_1 k1. From Bhāskarā’s, lemma we need a + b m a + bm a+bm to be evenly divisible by k 1 k_1 k1 and m 2 m^2 m2 to be as close to n n n as possible. The steps in the algorithm are,

-

Find an initial nearby solution to a 2 − n b 2 = k 1 a^2 - nb^2 = k_1 a2−nb2=k1 where a a a and b b b have no common divisors

-

Look for a + b m a+bm a+bm divisible by k k k and then select the m m m that minimizes ∣ m 2 − n ∣ |m^2-n| ∣m2−n∣

-

Get new values a ′ , b ′ a',b' a′,b′ and k ′ k' k′ from

a ′ = m a + n b ∣ k ∣ b ′ = a + b m ∣ k ∣ k ′ = m 2 − n k . \begin{align} a' &= \frac{ma+nb}{|k|} \\ b' &= \frac{a+bm}{|k|} \\ k' &= \frac{m^2-n}{k}. \end{align} a′b′k′=∣k∣ma+nb=∣k∣a+bm=km2−n.Repeat the second and third steps until k ′ = 1 k' = 1 k′=1.

Does the Chakravala ever end, or does the wheel keep on turning? Fortunately, the algorithm converges, that is, it eventually gets to k = 1 k=1 k=1. The proof is given by A. Bauval in "An elementary proof of the halting property for the Chakravala Algorithm".

But to make the Chakravala work requires understanding modular arithmetic.

Modular Arithmetic¶

In number theory it's often useful to describe a number by its remainder when divided by another number, so if

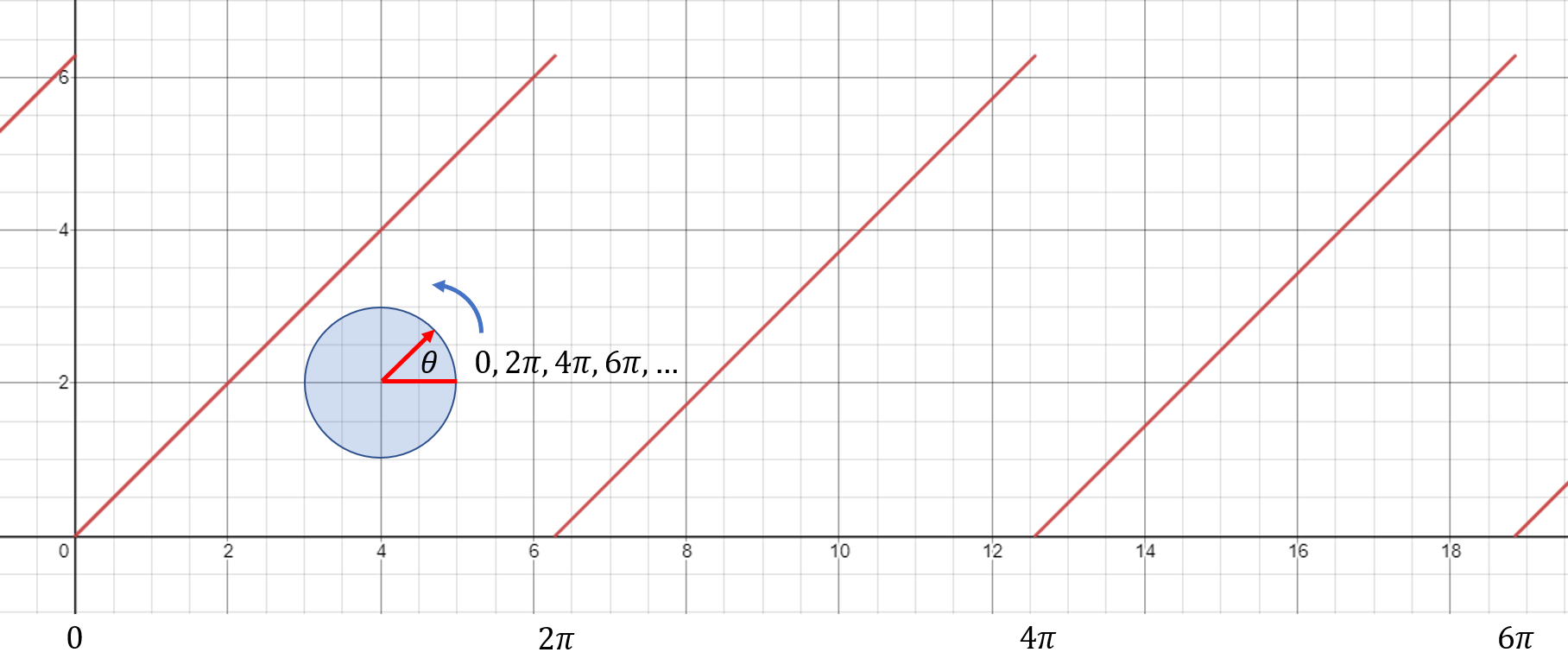

a = q n + r a = qn+r a=qn+rthen n n n goes into a a a q q q times with a remainder of r r r. An example is the angle when going around a circle:

If the circle has a radius of 1 1 1, then the angle θ \theta θ ranges from 0 0 0 to 2 π 2 \pi 2π, but once it gets back to the x x x-axis the remainder resets to 0 0 0. That is, you can't tell from looking at where the pointer is whether it's gone around zero times, once, twice, or more. The sloped lines in this plot represent the remainder of the angle after dividing by 2 π 2 \pi 2π. Usually, the numbers a , q , n a,q,n a,q,n, and r r r are integers and the equation is often written as

a = r mod ( n ) a = r \text{ mod}(n) a=r mod(n)meaning that the remainder when a a a is divided by n n n is r r r, or " a a a equals r r r modulo n n n".

If a = r 1 mod ( n ) a = r_1 \text{ mod}(n) a=r1 mod(n) and b = r 2 mod ( n ) b = r_2 \text{ mod}(n) b=r2 mod(n) then a + b = r 1 + r 2 mod ( n ) a+b = r_1 + r_2 \text{ mod}(n) a+b=r1+r2 mod(n), since

a = q 1 n + r 1 b = q 2 n + r 2 a + b = ( q 1 n + r 1 ) + ( q 2 n + r 2 ) = ( q 1 + q 2 ) n + ( r 1 + r 2 ) = r 1 + r 2 mod ( n ) \begin{align} a &= q_1 n + r_1 \\ b &= q_2n+r_2 \\ a+b &= (q_1 n + r_1) + (q_2 n + r_2) \\ &= (q_1 + q_2) n + (r_1 + r_2) \\ &= r_1 + r_2 \text{ mod}(n) \end{align} aba+b=q1n+r1=q2n+r2=(q1n+r1)+(q2n+r2)=(q1+q2)n+(r1+r2)=r1+r2 mod(n)For example, 14 = 4 mod ( 5 ) 14 = 4 \text{ mod}(5) 14=4 mod(5) and 17 = 2 mod ( 5 ) 17 = 2 \text{ mod}(5) 17=2 mod(5) so 14 + 17 = 31 = 1 mod ( 5 ) 14+17 = 31 = 1 \text{ mod}(5) 14+17=31=1 mod(5). Of course, adding 4 + 2 = 6 4+2 = 6 4+2=6 so you have to apply the modulus again to get 6 = 1 mod ( 5 ) 6 = 1 \text{ mod}(5) 6=1 mod(5). Subtraction works the same way with a − b = ( q 1 n + r 1 ) − ( q 2 n + r 2 ) a - b = (q_1 n + r_1) - (q_2 n + r_2) a−b=(q1n+r1)−(q2n+r2).

You can multiply numbers modulo n n n. Using the same notation from above,

a × b = ( q 1 n + r 1 ) × ( q 2 n + r 2 ) = q 1 q 2 n 2 + q 1 r 2 n + q 2 r 1 n + r 1 r 2 = ( q 1 q 2 n + q 1 r 2 + q 2 r 1 ) n + r 1 r 2 = r 1 r 2 mod ( n ) \begin{align} a \times b &= (q_1 n + r_1) \times (q_2 n + r_2) \\ &= q_1 q_2 n^2 + q_1 r_2 n + q_2 r_1 n + r_1 r_2 \\ &= (q_1 q_2 n + q_1 r_2 + q_2 r_1)n + r_1 r_2 \\ &= r_1 r_2 \text{ mod}(n) \end{align} a×b=(q1n+r1)×(q2n+r2)=q1q2n2+q1r2n+q2r1n+r1r2=(q1q2n+q1r2+q2r1)n+r1r2=r1r2 mod(n)So, 14 × 17 = 238 = 3 mod ( 5 ) 14 \times 17 = 238 = 3 \text{ mod} (5) 14×17=238=3 mod(5) and 4 × 2 = 8 = 3 mod ( 5 ) 4 \times 2 = 8 = 3 \text{ mod}(5) 4×2=8=3 mod(5).

The only arithmetic operation left is division. Since 10 = 4 mod ( 6 ) 10 = 4 \text{ mod}(6) 10=4 mod(6) it would be convenient if we could divide both sides by 2 2 2 to get 10 2 = 5 = 4 2 = 2 mod ( 6 ) \frac{10}{2} = 5 = \frac{4}{2} = 2 \text{ mod}(6) 210=5=24=2 mod(6), but clearly, that's wrong, 5 ≠ 2 mod ( 6 ) 5 \neq 2 \text{ mod}(6) 5=2 mod(6). The division operation that we're used to means that if

x y = z \frac{x}{y} = z yx=zthen

x = y z . x = yz. x=yz.If the solution to dividing x x x by y y y is z z z, then multiplication reverses this, so y y y times z z z must equal x x x. We need an equivalent for modulo division. Suppose there are two numbers z 1 z_1 z1 and z 2 z_2 z2 such that multiplication by y y y gives the same answer modulo n n n,

z 1 y = z 2 y mod ( n ) . z_1y = z_2y \text{ mod}(n). z1y=z2y mod(n).This means that z 1 y = q 1 n + r 1 z_1y = q_1 n + r_1 z1y=q1n+r1 and z 2 y = q 2 n + r 2 z_2y = q_2n + r_2 z2y=q2n+r2 for some q 1 , q 2 , r 1 q_1,q_2,r_1 q1,q2,r1 and r 2 r_2 r2. Since z 1 y = z 2 y mod ( n ) z_1y = z_2y \text{ mod}(n) z1y=z2y mod(n) then r 1 = r 2 r_1 = r_2 r1=r2, so

z 1 y = q 1 n = q 2 n = z 2 y z 1 y − z 2 y = ( z 1 − z 2 ) y = k n \begin{align} z_1y &= q_1n = q_2n = z_2y \\ z_1y - z_2y &= (z_1 - z_2)y = kn \end{align} z1yz1y−z2y=q1n=q2n=z2y=(z1−z2)y=knfor some integer k k k. We can find a solution to the division problem using the greatest common divisor of n n n and y y y.

The greatest common divisor (gcd) of two integers is the largest integer that divides both of them. To find the gcd, find the prime factors of each, and then take the product of all the common factors,

60 = 2 2 × 3 × 5 18 = 2 × 3 2 g c d ( 60 , 18 ) = 2 × 3 = 6 \begin{align} 60 &= 2^2 \times 3 \times 5 \\ 18 &= 2 \times 3^2 \\ gcd(60,18) &= 2 \times 3 = 6 \end{align} 6018gcd(60,18)=22×3×5=2×32=2×3=6Suppose the g c d ( n , y ) = d gcd(n,y) = d gcd(n,y)=d and that d ≠ y d \neq y d=y. The second condition means that y y y does not divide evenly into n n n. Divide n n n by d d d to get some integer g = n d g = \frac{n}{d} g=dn. Now g g g is also a divisor of n n n since d = n g d = \frac{n}{g} d=gn, but g g g can't be a divisor of y y y because if it were, then both d d d and g g g would be divisors of n n n, as would the product d g dg dg meaning that d d d wasn't really the greatest common divisor. So, if g = n d g = \frac{n}{d} g=dn doesn't go evenly into y y y, then it must divide z 1 − z 2 z_1 - z_2 z1−z2, since

( z 1 − z 2 ) y = k n . (z_1-z_2)y = kn. (z1−z2)y=kn.This means that

z 1 y = z 2 y mod ( n ) z_1y = z_2y \text{ mod}(n) z1y=z2y mod(n)only when

z 1 = z 2 mod ( n d ) . z_1 = z_2 \text{ mod}\left( \frac{n}{d} \right). z1=z2 mod(dn).So, a unique solution exists only when the g c d ( n , y ) = 1 gcd(n,y) = 1 gcd(n,y)=1. In this case, n n n and y y y are said to be relatively prime or coprime. Let's go back to the original problem of finding y − 1 = 1 y y^{-1} = \frac{1}{y} y−1=y1 such that x y − 1 = z mod ( n ) x y^{-1} = z \text{ mod}(n) xy−1=z mod(n). One way to find y − 1 y^{-1} y−1 would be to check every element of the set 1 , 2 , … , n {1,2, \ldots, n} 1,2,…,n until we find a solution. But there's a faster way using the greatest common divisor method discovered by Euclid.

The Euclidian Algorithm¶

Euclid's algorithm is a more practical method for finding the greatest common divisor of two numbers than listing their prime factors and then calculating the product of their common factors. Suppose you want to find g c d ( a , b ) gcd(a,b) gcd(a,b) where a > b a > b a>b. Now, a = q 1 b + r 1 a = q_1b + r_1 a=q1b+r1, and b = q 2 r 1 + r 2 b = q_2r_1 + r_2 b=q2r1+r2 for some q 1 , q 2 , r 1 , r 2 q_1,q_2,r_1,r_2 q1,q2,r1,r2. Write r 1 r_1 r1 in terms of r 2 r_2 r2: r 1 = q 3 r 2 + r 3 r_1 = q_3r_2 + r_3 r1=q3r2+r3. Maybe you find that r 3 = 0 r_3 = 0 r3=0, meaning that r 2 r_2 r2 is a divisor of r 1 r_1 r1. Then,

b = q 2 ( q 3 r 2 ) + r 2 = ( q 2 q 3 + 1 ) r 2 b = q_2(q_3r_2)+r_2 = (q_2q_3+1)r_2 b=q2(q3r2)+r2=(q2q3+1)r2and

a = q 1 b + r 1 = q 1 ( q 2 q 3 + 1 ) r 2 + r 1 = q 1 ( q 2 q 3 + 1 ) r 2 + q 3 r 2 = ( q 1 ( q 2 q 3 + 1 ) + 1 ) r 2 . \begin{align} a &= q_1b+r_1 = q_1(q_2q_3+1)r_2 + r_1 \\ &= q_1(q_2q_3+1)r_2 + q_3r_2 \\ &= (q_1(q_2q_3+1) + 1) r_2. \end{align} a=q1b+r1=q1(q2q3+1)r2+r1=q1(q2q3+1)r2+q3r2=(q1(q2q3+1)+1)r2.This means that r 2 r_2 r2 divides both a a a and b b b and if we let w = q 2 q 3 + 1 w = q_2q_3+1 w=q2q3+1 then b = w r 2 b = w r_2 b=wr2 and a = ( q 1 w + 1 ) r 2 a = (q_1w+1)r_2 a=(q1w+1)r2, so r 2 r_2 r2 is the largest divisor of both a a a and b b b.

Using the example from above, we'll find the g c d ( 60 , 18 ) gcd(60,18) gcd(60,18) using the Euclidean Algorithm:

60 = 3 × 18 + 6 18 = 3 × 6 + 0 ⇒ g c d ( 60 , 18 ) = 6. \begin{align} 60 &= 3 \times 18 + 6 \\ 18 &= 3 \times 6 + 0 \\ &\Rightarrow gcd(60,18) = 6. \end{align} 6018=3×18+6=3×6+0⇒gcd(60,18)=6.We get the answer in just two steps, and no factorization is needed. If r 3 r_3 r3 isn't zero, continue the process until some r n = 0 r_n = 0 rn=0.

The Euclidean Algorithm can be extended to solve problems such as

a x + b y = c . ax+by = c. ax+by=c.As an example, let's start by finding the greatest common divisor of 33 33 33 and 27 27 27,

33 = 1 × 27 + 6 27 = 4 × 6 + 3 6 = 2 × 3 + 0 ⇒ gcd ( 33 , 27 ) = 3. \begin{align} 33 &= 1 \times 27 + 6 \\ 27 &= 4 \times 6 + 3 \\ 6 &= 2 \times 3 + 0 \\ &\Rightarrow \text{gcd}(33,27) = 3. \end{align} 33276=1×27+6=4×6+3=2×3+0⇒gcd(33,27)=3.Now, suppose we want to solve

3 = 33 a + 27 b . 3 = 33a + 27b. 3=33a+27b.From the gcd calculation above,

6 = 33 − 1 × 27 , 3 = 27 − 4 × 6 \begin{align} 6 &= 33 - 1 \times 27, \\ 3 &= 27 - 4 \times 6 \\ \end{align} 63=33−1×27,=27−4×6Replace the 6 6 6 in the second equation with the one from the first to get

3 = 27 − 4 × ( 33 − 1 × 27 ) = − 4 × 33 + ( 1 + 4 ) × 27 = − 4 × 33 + 5 × 27. \begin{align} 3 &= 27 - 4 \times (33 - 1 \times 27) \\ &= -4 \times 33 + (1 + 4) \times 27 \\ &= -4 \times 33 + 5 \times 27. \end{align} 3=27−4×(33−1×27)=−4×33+(1+4)×27=−4×33+5×27.so a = − 4 a = -4 a=−4 and b = 5 b = 5 b=5.

Modular Division¶

Going back to the division equation above,

x y = z x = y z ⇒ x = y z + k n \begin{align} \frac{x}{y} &= z \\ x &= y z \\ \Rightarrow x &= y z + k n \end{align} yxx⇒x=z=yz=yz+knIn other words, if the solution to dividing x x x by y y y is z z z, then in modular arithmetic terms (modulo n n n), x x x is y y y times z z z plus some constant multiple k k k of n n n. This is exactly the extended Euclidean algorithm for the gcd that we just did. If y y y and n n n are coprime ( g c d ( n , y ) = 1 gcd(n,y)=1 gcd(n,y)=1) then there are integers r r r and s s s such that

1 = r y + s n 1 = ry + sn 1=ry+snand

z = r x + t n k = s z − t y \begin{align} z &= rx + tn \\ k &= sz - ty \end{align} zk=rx+tn=sz−tyfor every integer t t t. Here's the trick - when you calculate 1 = r y + s n mod ( n ) 1 = ry + sn \text{ mod} (n) 1=ry+sn mod(n) the term with s n sn sn is zero because n n n is a divisor. So what's left is

1 = r y mod ( n ) 1 = ry \text{ mod}(n) 1=ry mod(n)which means that

r = 1 y mod ( n ) r = \frac{1}{y} \text{ mod}(n) r=y1 mod(n)so r r r is the inverse of y y y.

If g c d ( n , y ) = d > 1 gcd(n,y) = d > 1 gcd(n,y)=d>1 and x x x is an integer multiple of d d d, then

z = r + t n d k = s − t y d , \begin{align} z &= r + t \frac{n}{d} \\ k &= s - t \frac{y}{d}, \end{align} zk=r+tdn=s−tdy,but there won't be a unique solution modulo n n n (but there will be modulo n / d n/d n/d). This means that we have methods for calculating addition, subtraction, multiplication, and under special conditions, division modulo n n n.

The algorithm¶

To solve the equation

a 2 − n b 2 = 1 a^2-nb^2 = 1 a2−nb2=1for a given positive integer n n n, start with values for [ a , b , k ] [a,b,k] [a,b,k] and g c d ( a , b ) = 1 gcd(a,b)=1 gcd(a,b)=1. An easy choice for b b b is 1 1 1 since setting a a a to the next larger integer to n \sqrt{n} n makes k k k small.

- Find values of m m m such that k k k divides a + b m a + bm a+bm, and select the m m m that minimizes ∣ m 2 − n ∣ |m^2 - n| ∣m2−n∣.

- Recompute

If k ′ = 1 k' = 1 k′=1 we have a solution, otherwise find a new m m m satisfying the constraint and iterate until k ′ = 1 k' = 1 k′=1.

Finding m m m such that k k k divides a + b m a+bm a+bm means that there is some j j j such that

a + b m = j k a + bm = jk a+bm=jkor

b m = − a mod ( k ) bm = -a \; \text{mod}(k) bm=−amod(k)Using the extended Euclidean algorithm, we can find 1 b mod k \frac{1}{b} \text{ mod } k b1 mod k and an integer t t t such that

t = ( − a 1 b ) mod ( k ) . t = \left(-a \frac{1}{b} \right) \text{ mod}(k). t=(−ab1) mod(k).The m m m that satisfies a + b m = 0 mod ( k ) a + bm = 0 \text{ mod}(k) a+bm=0 mod(k) and minimizes ∣ m 2 − n ∣ |m^2 - n| ∣m2−n∣ will have a remainder of t t t when divided by k k k, so it's just a matter of finding the multiple j j j,

Let n = 17 n = 17 n=17 and start with [ a , b , k ] = [ 5 , 1 , 8 ] [a,b,k] = [5,1,8] [a,b,k]=[5,1,8], so 5 2 − 17 × 1 2 = 8 5^2 - 17 \times 1^2 = 8 52−17×12=8. Then we want 5 + 1 × m = 8 j 5 + 1 \times m = 8j 5+1×m=8j. This is equivalent to

1 × m = − 5 = 3 mod ( 8 ) . 1 \times m = -5 = 3 \; \text{mod}(8). 1×m=−5=3mod(8).When b = 1 b=1 b=1 the problem is trivial because m m m has to be in the set { 3 , 11 , 19 , 27 , … } = { 8 − 5 , 16 − 5 , 24 − 5 , 32 − 5 , … } \{3,11,19,27, \ldots \} = \{8-5,16-5,24-5,32-5, \ldots \} {3,11,19,27,…}={8−5,16−5,24−5,32−5,…}. For n = 17 n=17 n=17, ∣ m 2 − n ∣ |m^2-n| ∣m2−n∣ is minimized when m = 3 m=3 m=3. Update a , b , a,b, a,b, and k k k,

a ′ ← m a + n b ∣ k ∣ = 3 × 5 + 17 × 1 ∣ 8 ∣ = 4 b ′ ← a + b m ∣ k ∣ = 5 + 1 × 3 ∣ 8 ∣ = 1 k ′ ← m 2 − n k = 3 2 − 17 8 = − 1 \begin{align} a' &\leftarrow \frac{ma+nb}{|k|} = \frac{3 \times 5 + 17 \times 1}{|8|} = 4 \\ b' &\leftarrow \frac{a+bm}{|k|} = \frac{5 + 1 \times 3}{|8|} = 1 \\ k' &\leftarrow \frac{m^2-n}{k} = \frac{3^2 - 17}{8} = -1 \end{align} a′b′k′←∣k∣ma+nb=∣8∣3×5+17×1=4←∣k∣a+bm=∣8∣5+1×3=1←km2−n=832−17=−1Calculating a new value for m m m, we need 4 + 1 × m 4 + 1 \times m 4+1×m to be divisible by k = − 1 k = -1 k=−1, and so any value of m m m will do, and the value that minimizes ∣ m 2 − n ∣ |m^2 - n| ∣m2−n∣ is 4 4 4. Updating the values for a , b a,b a,b, and k k k give a = 33 a = 33 a=33, b = 8 b = 8 b=8 and k = 1 k = 1 k=1, so the algorithm stops with

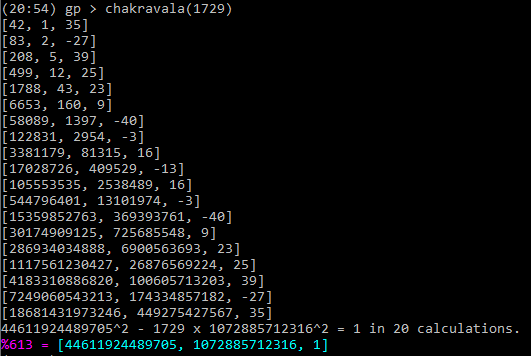

3 3 2 − 17 × 8 2 = 1 1089 − 17 × 64 = 1089 − 1088 = 1. \begin{align} 33^2 - 17 \times 8^2 &= 1 \\ 1089 - 17 \times 64 &= 1089 - 1088 = 1. \end{align} 332−17×821089−17×64=1=1089−1088=1.Using the PARI/GP language, the code chakravala.gp (saved on GitHub) finds the smallest values of a a a and b b b for a given n n n. This is a screenshot of the solution to Chris Havens' problem with the Ramanujan-Hardy Taxicab number 1729:

The Prison Mathematics Project¶

The Prison Mathematics Projects likes to hear from people willing to volunteer time to help inmates improve their math skills. From the website,

"In early 2012, a prisoner by the name Christopher Havens began studying mathematics for the very first time within the prison inside of prison. Christopher was in a form of isolation that we call solitary confinement… prisoners know it as “the hole”. Having no other form of stimulation, mathematics occupied every hour of Christopher’s days, lasting the better part of a year until he was released back into the general population. In so many cases, the negative effects of prolonged isolation manifests itself through the behaviors in both the short and the long term. However, this case is one where a mix of isolation and the transformative powers of mathematics caused Christopher to undergo a steady chain of personal growth while igniting within him a passion for mathematics. "

If you have some ability in mathematics and would like to volunteer, you can submit your name and email address, and the PMP will connect you with an inmate to become their "pen pal". Donations are also greatly appreciated.

📬 Subscribe and stay in the loop. · Email · GitHub · Forum · Facebook

© 2020 – 2025 Jan De Wilde & John Peach