keywords: Betz Limit, wind energy, thermodynamics, Bernoulli's principle, wind-powered vehicles

"Excuse me, surely you are related to the Deer Family, are you not?"

"Yes," said the pushmi-pullyu—"to the Abyssinian Gazelles and the Asiatic Chamois—on my mother's side. My father's great-grandfather was the last of the Unicorns."

In Violation of the Laws of Thermodynamics¶

The Push-me-pull-you is a perpetual motion machine in strict violation of the Laws of Thermodynamics. There will be consequences.

The three Laws of Thermodynamics are:

- You can't play unless you bet, and you can't win. An increase in energy in a system is the same as the energy given to a system in the form of heat or work. Energy cannot be created or destroyed, only changed. The amount of energy given to a system is the same amount of energy taken from the surroundings. In other words, you can't get more energy out of something than you put into it.

- The most you can hope for is to break even. Given a pair of systems touching with different temperatures, heat will flow from hot to cold until the temperature of the systems becomes equal. Energy flows from a more energetic system to a less energetic system, and entropy always increases.

- You can't break even and you can't stop playing. When a system has a temperature of absolute zero (on the Kelvin temperature scale) the entropy is zero. Entropy is the energy that cannot be used to do work. Entropy approaches a constant as the system temperature approaches absolute zero.

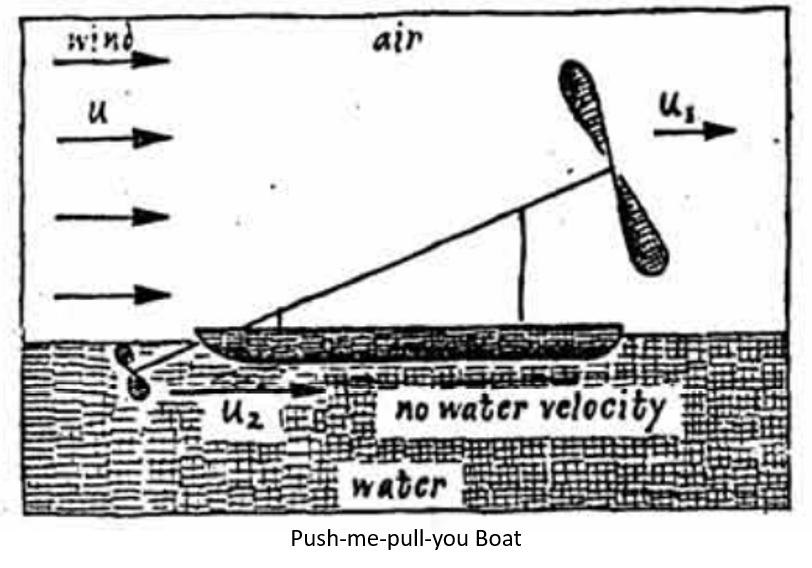

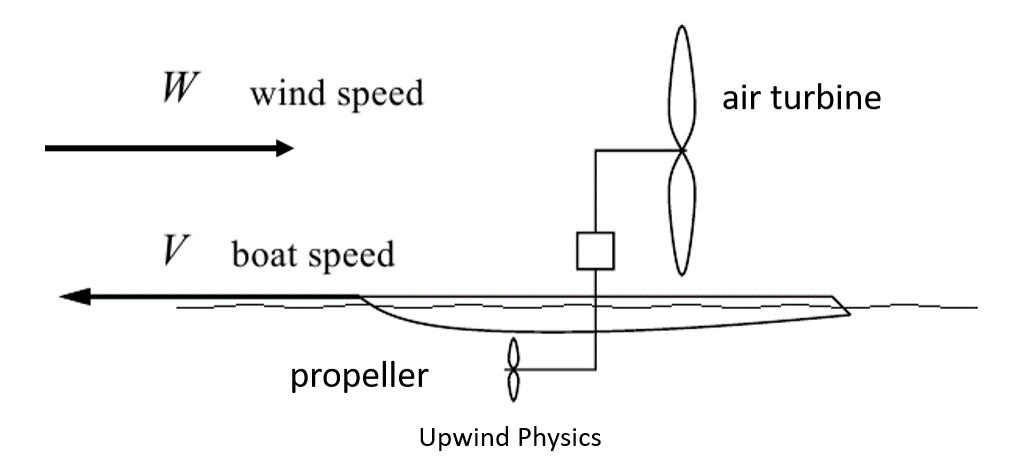

The Push-me-pull-you is a boat with two propellers connected by a drive shaft. One propeller is above the water and spins with the wind. It turns the drive shaft which rotates a second propeller in the water. If you let the air propeller face the wind, then it will cause the propeller in the water to pull the boat forward into the wind.

The apparent wind speed is the speed of the wind plus the speed of the boat, so the air propeller spins faster, spinning the water propeller faster and moving the boat more quickly through the water - into the wind! Now the apparent wind is even greater, so the boat goes faster and faster!

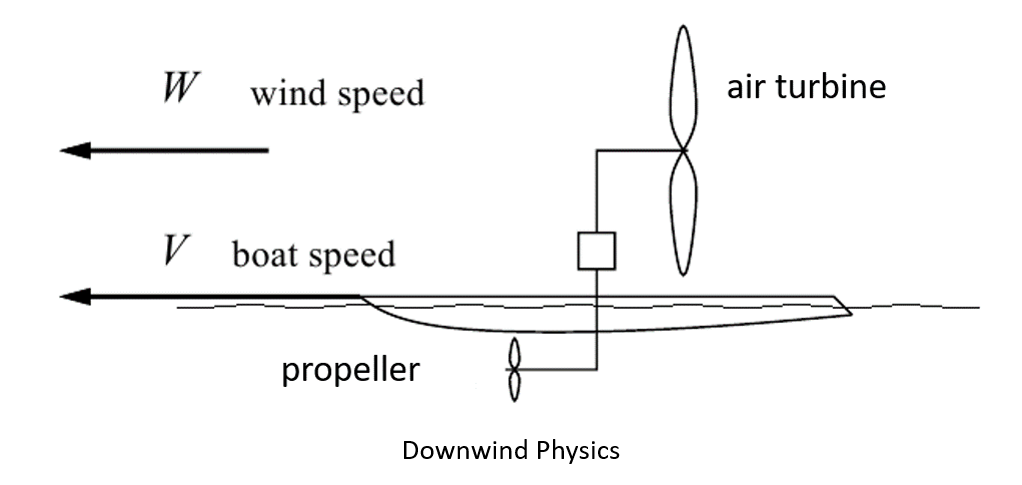

Turn the boat so it faces downwind, and then drag forces on the boat will begin to push the boat in the direction the wind is blowing. The propeller in the water spins because the boat is moving in the water, and the air propeller spinning acts as a blower, causing the boat to go faster downwind.

The Push-me-pull-you is clearly a perpetual motion machine violating at least one of those Laws of Thermodynamics. But if your ancestors are Abyssinian Gazelles and Unicorns maybe you've got some magic.

An Iceboat Faster than the Wind Downwind¶

Is it possible for a boat to sail downwind faster than the wind? If the boat heads directly downwind, then at best, it could reach the same speed as the wind if no other drag forces were acting on the boat. A balloon floating in the air travels at the same speed as the wind, but a boat would have trouble achieving wind speed because of the drag forces of the water on the hull.

Ice boats speed along at many times the true wind speed when sailing at an angle to the wind direction. According to this article, "Iceboats can sail as close as 7 degrees off the apparent wind. Ice boats can achieve speeds as high as ten times the wind speed in good conditions."

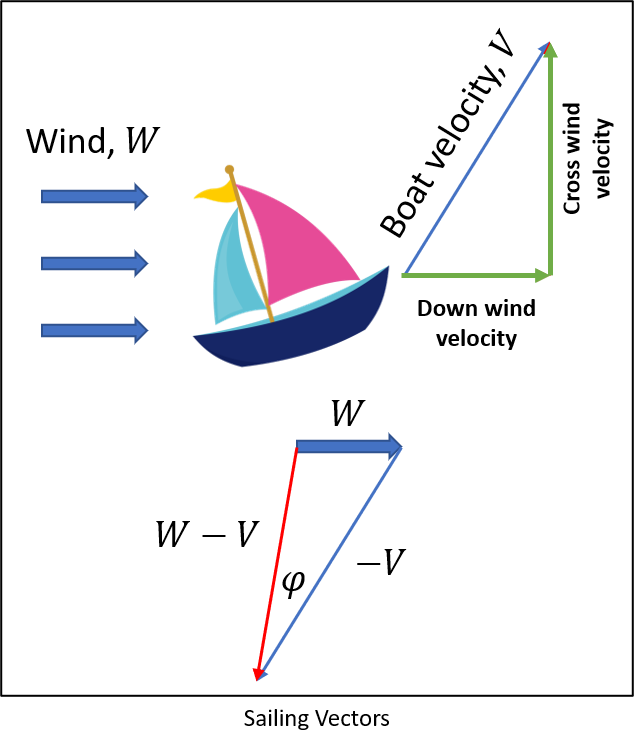

If the iceboat sails at an angle to the true wind direction with velocity vector V V V, then the sailor will feel an apparent wind force in the opposite direction, − V -V −V. Combine − V -V −V with the true wind vector W W W to get W − V W-V W−V, the apparent wind on the iceboat (shown as the red vector).

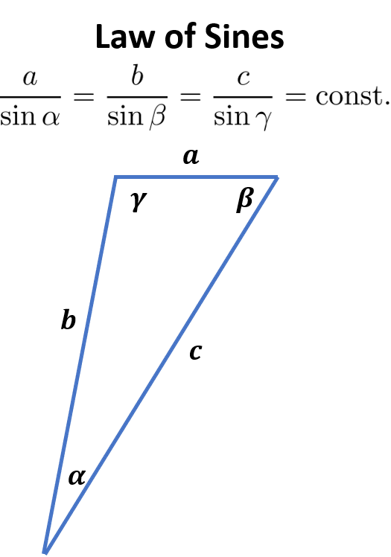

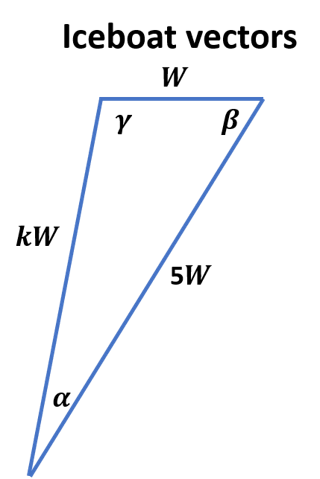

The boat will only be able to sail within some angle α \alpha α to this apparent wind vector. If we assume V = 5 W V = 5W V=5W (which seems more reasonable than the 10 × 10 \times 10× from the link above), we can use the law of sines to calculate the other angles in the triangle,

For the iceboat, the angle between the boat direction and the apparent wind is α = 7 ∘ \alpha = 7^\circ α=7∘, and we have sides a a a, the wind vector, and c = 5 W c = 5W c=5W, the boat travel direction. Using the law of sines, we can calculate angle γ \gamma γ,

Using the larger of the two possible solutions (see "The ambiguous case of triangle solution") for γ \gamma γ means β = 180 − ( α + γ ) = 30.5 4 ∘ \beta = 180 - (\alpha + \gamma) = 30.54^{\circ} β=180−(α+γ)=30.54∘, which is the angle between the boat direction and the true wind vector. The downwind component of the iceboat velocity vector is 5 cos β = 4.31 5 \; \cos \beta = 4.31 5cosβ=4.31, meaning the iceboat travels more than 4 4 4 times the speed of wind downwind! The apparent wind velocity is k = 5.82 k = 5.82 k=5.82 for this example.

Push-Me-Pull-You Physics¶

In 1752 Leonhard Euler discovered Bernoulli's Principle of Fluid Dynamics,

p + 1 2 ρ v 2 + ρ g h = const. p + \frac{1}{2}\rho v^2 + \rho g h = \text{const.} p+21ρv2+ρgh=const.where

∙ p = pressure, N m 2 = k g m ⋅ s 2 ∙ ρ = density, k g m 3 ∙ v = velocity, m s ∙ g = gravitational acceleration constant, 9.81 m s 2 ∙ h = change in height, m \begin{aligned} \bullet \; p &= \text{pressure, } \frac{N}{m^2} = \frac{kg}{m \cdot s^2} \\ \bullet \; \rho &= \text{density, } \frac{kg}{m^3} \\ \bullet \; v &= \text{velocity, } \frac{m}{s} \\ \bullet \; g &= \text{gravitational acceleration constant, } 9.81 \; \frac{m}{s^2} \\ \bullet \; h &= \text{change in height, } m \\ \end{aligned} ∙p∙ρ∙v∙g∙h=pressure, m2N=m⋅s2kg=density, m3kg=velocity, sm=gravitational acceleration constant, 9.81s2m=change in height, mDaniel Bernoulli had earlier discovered that the pressure and the velocity of a fluid are inversely related, which means as the velocity of a fluid increases the pressure drops. Euler extended this concept to include the density ρ \rho ρ and included a third term, ρ g h \rho g h ρgh, to account for a change in height of the flow.

Water is considered to be an incompressible fluid. Imagine filling a container with water and then trying to squeeze the container after sealing it. Intuitively, it's obvious the total volume won't change no matter how hard you try to compress the container.

It turns out that air is mostly incompressible as well if the speed is not too high. This means that the air density ρ \rho ρ remains constant even as the velocity and pressure change.

For the Push-me-pull-you, the height of the stream of air through the wind turbine, and the height of the water through the propeller doesn't change much. The equation can be simplified to the form Bernoulli discovered,

p + q = p 0 p + q = p_0 p+q=p0where q q q is the dynamic pressure, q = 1 2 ρ v 2 q = \frac{1}{2}\rho v^2 q=21ρv2, p p p is called the static pressure, and p 0 p_0 p0 is the total pressure which remains constant.

Using Bernoulli's Principle we can calculate the change in pressure through the wind turbine. In 1978, B. L. Blackford published a paper titled "The physics of a push-me pull-you boat". It wasn't the first to talk about connecting a wind turbine to a propeller to move the boat directly into the wind, but his paper is an early example. The equations here are based on his paper.

Far upstream and far downstream of the wind turbine, the pressure is P ∞ P_\infty P∞. The wind speed upstream is v u v_u vu, and downstream it's v d v_d vd. Directly in front of the turbine, (to the left) the pressure is P L P_L PL and the speed is v L v_L vL while just behind the turbine (to the right) the pressure is P R P_R PR and the speed is v R v_R vR. Using Bernoulli's Principle,

P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v u 2 = P L + 1 2 ρ v L 2 P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v d 2 = P R + 1 2 ρ v R 2 . \begin{aligned} P_\infty + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_u^2 &= P_L + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_L^2 \\ P_\infty + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_d^2 &= P_R + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_R^2. \end{aligned} P∞+21ρvu2P∞+21ρvd2=PL+21ρvL2=PR+21ρvR2.Taking the difference,

( P L + 1 2 ρ v L 2 ) − ( P R + 1 2 ρ v R 2 ) = ( P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v u 2 ) − ( P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v d 2 ) = 1 2 ρ ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) . \begin{aligned} &\left(P_L + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_L^2 \right) - \left( P_R + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_R^2 \right) \\ &= \left( P_\infty + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_u^2 \right) - \left( P_\infty + \frac{1}{2}\rho v_d^2 \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho \left(v_u^2 -v_d^2 \right). \end{aligned} (PL+21ρvL2)−(PR+21ρvR2)=(P∞+21ρvu2)−(P∞+21ρvd2)=21ρ(vu2−vd2).The change in pressure is half the density times the difference of the squares of the air velocities upstream and downstream of the turbine.

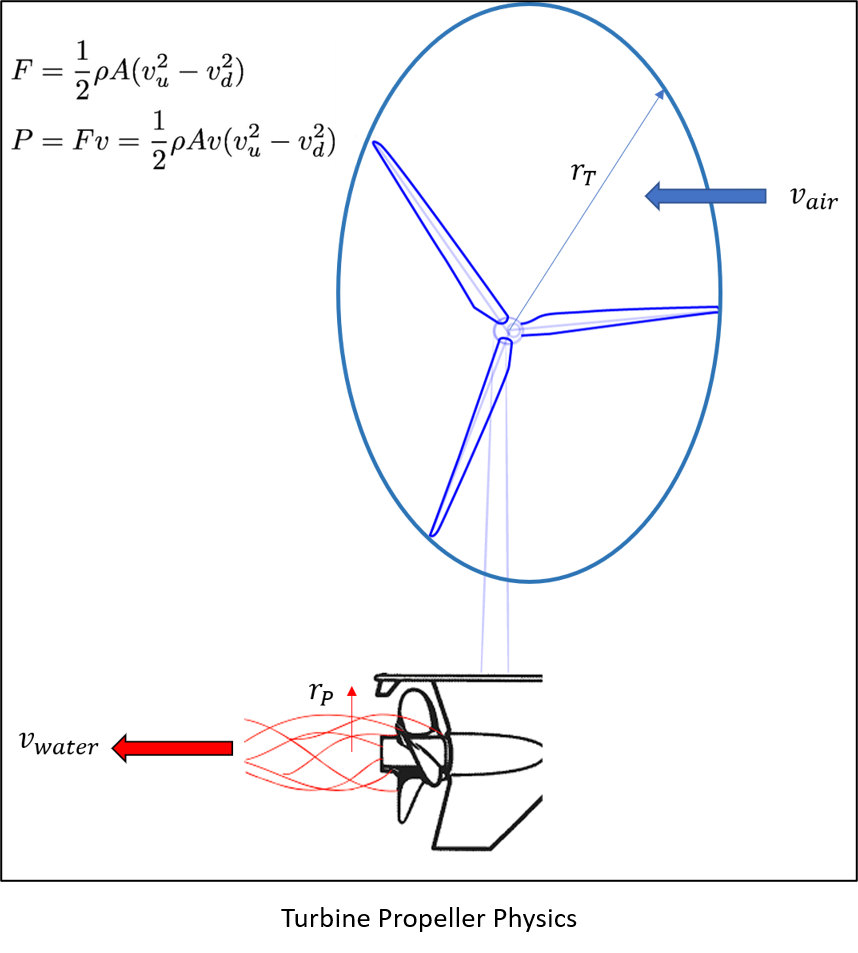

In the previous post, Betz the Limit, we found the force of the wind on the turbine,

F = 1 2 ρ A ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) F = \frac{1}{2} \rho A (v_u^2 - v_d^2) F=21ρA(vu2−vd2)where

∙ ρ a i r = air density, 1.225 k g m 3 ∙ A = the swept area of the rotor, A = π r 2 , m ∙ v u = air velocity upstream of the turbine, m s ∙ v d = air velocity downstream of the turbine, m s \begin{aligned} &\bullet \; \rho_{air} = \text{air density, } 1.225 \frac{kg}{m^3} \\ &\bullet \; A = \text{the swept area of the rotor, } \; A = \pi r^2, \; m \\ &\bullet \; v_u = \text{air velocity upstream of the turbine, } \frac{m}{s} \\ &\bullet \; v_d = \text{air velocity downstream of the turbine, } \frac{m}{s} \\ \end{aligned} ∙ρair=air density, 1.225m3kg∙A=the swept area of the rotor, A=πr2,m∙vu=air velocity upstream of the turbine, sm∙vd=air velocity downstream of the turbine, smThe power extracted by the turbine is

P = F v P = Fv P=Fvwhere v v v is the wind velocity through the turbine.

The same equations can be applied to the propeller in the water by using the density of water, ρ w a t e r = 997 k g m 3 \rho_{water} = 997 \frac{kg}{m^3} ρwater=997m3kg. Usually, currents are flowing, but we can take the reference frame to be a particle of water, so the boat moves relative to that point. In any case, the wind speed and the boat speed will generally be quite a bit faster than the speed of the water.

In the picture above, the wind turbine connects to the propeller through some mechanical linkage, and for this analysis, we'll assume there is no energy lost. It's not a bad assumption - most drive trains have efficiencies above 95%, and often 98%. More importantly, we need to account for the efficiencies of the wind turbine and the propeller, neither of which can exceed the Betz Limit. As the wind moves through the turbine (or the water through the propeller), the speed of the fluid changes. Let's call the ratio α T \alpha_T αT of the wind speed at the turbine, v T v_T vT, to the upstream windspeed, v u v_u vu,

α T = v T v u . \alpha_T = \frac{v_T}{v_u}. αT=vuvT.The force F T F_T FT on the wind turbine is

F T = ρ a i r A T v ( v u − v d ) = 1 2 ρ a i r A T ( v u + v d ) ( v u − v d ) \begin{aligned} F_T &= \rho_{air} A_T v (v_u - v_d) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho_{air} A_T (v_u + v_d) (v_u - v_d) \end{aligned} FT=ρairATv(vu−vd)=21ρairAT(vu+vd)(vu−vd)Substituting v T = α T v u v_T = \alpha_T v_u vT=αTvu,

F T = 1 2 ρ a i r A T ( v u + α T v u ) ( v u − α T v u ) = 1 2 ρ a i r A T v u 2 ( 1 − α T 2 ) \begin{aligned} F_T &= \frac{1}{2} \rho_{air}A_T (v_u + \alpha_T v_u)(v_u - \alpha_T v_u) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho_{air}A_T v_u^2 (1-\alpha_T^2) \end{aligned} FT=21ρairAT(vu+αTvu)(vu−αTvu)=21ρairATvu2(1−αT2)Conservation of mass requires that at every point in the stream tube the area times the velocity (times density) must remain constant,

A u v u = α T A T v u = A d v d . A_u v_u = \alpha_T A_T v_u = A_d v_d. Auvu=αTATvu=Advd.Using Bernoulli's Principle ( P + 1 2 ρ v 2 = const. P + \frac{1}{2}\rho v^2 = \text{const.} P+21ρv2=const.),

P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v u 2 = P L + 1 2 ρ [ v u ( 1 − α T ) ] 2 . P_\infty + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_u^2 = P_L + \frac{1}{2} \rho [v_u (1-\alpha_T)]^2. P∞+21ρvu2=PL+21ρ[vu(1−αT)]2. P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v d 2 = P R + 1 2 ρ [ v u ( 1 − α T ) ] 2 . P_\infty + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_d^2 = P_R + \frac{1}{2} \rho [v_u (1-\alpha_T)]^2. P∞+21ρvd2=PR+21ρ[vu(1−αT)]2.The pressure change across the wind turbine is the difference of these two equations,

Δ P = P L − P R ( P L + 1 2 ρ [ α T v u ] 2 ) − ( P R + 1 2 ρ [ α T v u ] 2 ) = ( P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v u 2 ) − ( P ∞ + 1 2 ρ v d 2 ) = 1 2 ρ ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) . \begin{aligned}\Delta P &= P_L - P_R \\ \left( P_L + \frac{1}{2} \rho [\alpha_T v_u]^2 \right) - \left( P_R + \frac{1}{2} \rho [\alpha_T v_u]^2 \right) &= \left( P_\infty + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_u^2 \right) - \left( P_\infty + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_d^2 \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho (v_u^2 - v_d^2). \\ \end{aligned} ΔP(PL+21ρ[αTvu]2)−(PR+21ρ[αTvu]2)=PL−PR=(P∞+21ρvu2)−(P∞+21ρvd2)=21ρ(vu2−vd2).The force on the turbine is the power times the swept area of the turbine,

F = P A T = 1 2 ρ A T ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) . F = PA_T = \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (v_u^2 - v_d^2). F=PAT=21ρAT(vu2−vd2).Momentum must also be conserved, so

F = ρ A u v u 2 − ρ A d v d 2 . F = \rho A_u v_u^2 - \rho A_d v_d^2. F=ρAuvu2−ρAdvd2.Using these two formulas for the force on the turbine,

1 2 ρ A T ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) = ρ A u v u 2 − ρ A d v d 2 . \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (v_u^2 - v_d^2) = \rho A_u v_u^2 - \rho A_d v_d^2. 21ρAT(vu2−vd2)=ρAuvu2−ρAdvd2.Multiplying both sides by 2 2 2 and factoring out the density ρ \rho ρ gives

A T v u 2 − A T v d 2 = 2 A u v u 2 − A d v d 2 . A_T v_u^2 - A_T v_d^2 = 2A_u v_u^2 - A_d v_d^2. ATvu2−ATvd2=2Auvu2−Advd2.We can use the conservation of mass equation above to solve for the downstream velocity, v d v_d vd, in terms of the wind speed upstream of the turbine, v u v_u vu,

1 2 ρ A T ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) = ρ A u v u 2 − ρ A d v d 2 1 2 A T v u 2 − 1 2 A T v d 2 = A u v u 2 − A d v d 2 1 2 A T v u 2 − A u v u 2 = 1 2 A T v d 2 − A d v d 2 1 2 A T v u 2 − α T A T v u 2 = 1 2 A T v d 2 − α T A T v u v d 1 2 v u 2 − α T v u 2 = 1 2 v d 2 − α T v u v d v u 2 − 2 α T v u 2 = v d 2 − 2 α T v u v d v d 2 − 2 α T v u v d − ( 1 − 2 α T ) v u 2 = 0. \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (v_u^2 - v_d^2) &= \rho A_u v_u^2 - \rho A_d v_d^2 \\ \frac{1}{2} A_Tv_u^2 - \frac{1}{2} A_T v_d^2 &= A_u v_u^2 - A_d v_d^2 \\ \frac{1}{2} A_Tv_u^2 - A_u v_u^2 &= \frac{1}{2} A_T v_d^2 - A_d v_d^2 \\ \frac{1}{2} A_Tv_u^2 - \alpha_T A_T v_u^2 &= \frac{1}{2} A_T v_d^2 - \alpha_T A_T v_u v_d \\ \frac{1}{2} v_u^2 - \alpha_T v_u^2 &= \frac{1}{2} v_d^2 - \alpha_T v_u v_d \\ v_u^2 - 2 \alpha_T v_u^2 &= v_d^2 - 2 \alpha_T v_u v_d \\ v_d^2 - 2 \alpha_T v_u v_d &- (1 - 2 \alpha_T) v_u^2 = 0. \end{aligned} 21ρAT(vu2−vd2)21ATvu2−21ATvd221ATvu2−Auvu221ATvu2−αTATvu221vu2−αTvu2vu2−2αTvu2vd2−2αTvuvd=ρAuvu2−ρAdvd2=Auvu2−Advd2=21ATvd2−Advd2=21ATvd2−αTATvuvd=21vd2−αTvuvd=vd2−2αTvuvd−(1−2αT)vu2=0.This is a quadratic equation in v d v_d vd, which we can solve using the quadratic formula. Let B = − 2 α T v u B = -2\alpha_T v_u B=−2αTvu and C = − ( 1 − 2 α T ) v u 2 C = -(1-2 \alpha_T)v_u^2 C=−(1−2αT)vu2,

v d = 1 2 ( − B ± B 2 − 4 C ) = 1 2 ( 2 α T v u ± 4 α T 2 v u 2 + 4 ( 1 − 2 α T ) v u 2 ) = ( α T v u ± v u α T 2 + ( 1 − 2 α T ) ) = ( α T v u ± v u ( α T − 1 ) 2 ) = α T v u ± ( α T − 1 ) v u = { ( 2 α T − 1 ) v u , v u } . \begin{aligned} v_d &= \frac{1}{2}\left( -B \pm \sqrt{B^2-4C} \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\left( 2 \alpha_T v_u \pm \sqrt{ 4 \alpha_T^2 v_u^2 + 4 (1-2\alpha_T)v_u^2} \right) \\ &= \left( \alpha_T v_u \pm v_u \sqrt{ \alpha_T^2 + (1-2\alpha_T)} \right) \\ &= \left( \alpha_T v_u \pm v_u \sqrt{ (\alpha_T - 1)^2} \right) \\ &= \alpha_T v_u \pm (\alpha_T - 1) v_u \\ &= \{ (2 \alpha_T - 1) v_u, v_u \}. \end{aligned} vd=21(−B±B2−4C)=21(2αTvu±4αT2vu2+4(1−2αT)vu2)=(αTvu±vuαT2+(1−2αT))=(αTvu±vu(αT−1)2)=αTvu±(αT−1)vu={(2αT−1)vu,vu}.The second solution, v d = v u v_d = v_u vd=vu happens only if nothing happens to slow the wind down, and no energy is extracted.

Power Extracted and Net Forward Thrust¶

The downstream wind velocity through the turbine has slowed to

v d = ( 2 α T − 1 ) v u v_d = (2 \alpha_T - 1) v_u vd=(2αT−1)vuso the force on the turbine is

F = 1 2 ρ A T ( v u 2 − v d 2 ) = 1 2 ρ A T ( v u 2 − ( 2 α T − 1 ) 2 v u 2 ) = 1 2 ρ A T ( 1 − ( 2 α T − 1 ) 2 ) v u 2 = 1 2 ρ A T ( 1 − ( 4 α T 2 − 4 α T + 1 ) ) v u 2 = 1 2 ρ A T ( − 4 α T 2 + 4 α T ) v u 2 = 2 ρ A T α T ( 1 − α T ) v u 2 . \begin{aligned} F &= \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (v_u^2 - v_d^2) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (v_u^2 - (2 \alpha_T - 1)^2v_u^2) \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (1 - (2 \alpha_T - 1)^2) v_u^2 \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (1 - (4 \alpha_T^2 - 4 \alpha_T + 1)) v_u^2 \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \rho A_T (-4 \alpha_T^2 + 4 \alpha_T) v_u^2 \\ &= 2 \rho A_T \alpha_T (1 - \alpha_T) v_u^2. \\ \end{aligned} F=21ρAT(vu2−vd2)=21ρAT(vu2−(2αT−1)2vu2)=21ρAT(1−(2αT−1)2)vu2=21ρAT(1−(4αT2−4αT+1))vu2=21ρAT(−4αT2+4αT)vu2=2ρATαT(1−αT)vu2.Power is force times air velocity at the turbine,

P = F ( 1 − α T ) v u = 2 ρ A T α T ( 1 − α T ) 2 v u 3 . P = F (1 - \alpha_T) v_u = 2 \rho A_T \alpha_T (1-\alpha_T)^2 v_u^3. P=F(1−αT)vu=2ρATαT(1−αT)2vu3.Differentiating the power with respect to the parameter α T \alpha_T αT,

d P d α T = 2 ρ A T ( 2 α T ( α T − 1 ) + ( 1 − α T ) 2 ) v u 3 = 2 ρ A T ( 3 α T 2 − 4 α T + 1 ) v u 3 , \begin{aligned} \frac{dP}{d \alpha_T} &= 2 \rho A_T \left( 2 \alpha_T (\alpha_T - 1) + (1 - \alpha_T)^2 \right) v_u^3 \\ &= 2 \rho A_T \left( 3 \alpha_T^2 - 4 \alpha_T + 1 \right) v_u^3, \end{aligned} dαTdP=2ρAT(2αT(αT−1)+(1−αT)2)vu3=2ρAT(3αT2−4αT+1)vu3,which has a critical point at α T = 1 3 \alpha_T = \frac{1}{3} αT=31, giving the maximum efficiency

η m a x = P m a x 1 2 ρ A T v u 3 = 2 ρ A T α T ( 1 − α T ) 2 v u 3 1 2 ρ A T v u 3 = 4 1 3 ( 1 − 1 3 ) 2 = 16 27 \begin{aligned} \eta_{max} &= \frac{P_{max}}{\frac{1}{2} \rho A_T v_u^3} \\ &= \frac{2 \rho A_T \alpha_T (1-\alpha_T)^2 v_u^3}{\frac{1}{2} \rho A_T v_u^3} \\ &= 4 \frac{1}{3} \left( 1 - \frac{1}{3} \right)^2 \\ &= \frac{16}{27} \end{aligned} ηmax=21ρATvu3Pmax=21ρATvu32ρATαT(1−αT)2vu3=431(1−31)2=2716which is the same result we found in Betz The Limit. Using α T = 1 3 \alpha_T = \frac{1}{3} αT=31,

P m a x = 2 ρ A T 4 27 v u 3 = 8 27 ρ A T v u 3 = 8 ρ A T v T 3 , P_{max} = 2 \rho A_T \frac{4}{27} v_u^3 = \frac{8}{27} \rho A_T v_u^3 = 8 \rho A_T v_T^3, Pmax=2ρAT274vu3=278ρATvu3=8ρATvT3,and

F m a x P ( 1 − α T v u ) = 4 9 ρ A T v u 2 = 4 3 ρ A T v T 2 . F_{max} \frac{P}{(1-\alpha_T v_u)} = \frac{4}{9} \rho A_T v_u^2 = \frac{4}{3} \rho A_T v_T^2. Fmax(1−αTvu)P=94ρATvu2=34ρATvT2.The same equations can be derived for the propeller, except we're assuming the water speed is zero before the propeller applies thrust. This means that the water speed downstream is twice the speed at the propeller.

Taking the difference between the thrust of the propeller and the force on the wind turbine gives the net forward thrust,

F net = ρ air A T v air 2 ( 0.56 ( ρ air A T ρ water A P ) 1 / 3 − 4 9 ) . F_{\text{net}} = \rho_{\text{air}} A_T v_{\text{air}}^2 \left( 0.56 \left( \frac{\rho_{\text{air}} A_T }{\rho_{\text{water}} A_P} \right)^{1/3} - \frac{4}{9} \right). Fnet=ρairATvair2(0.56(ρwaterAPρairAT)1/3−94).This case assumes ideal efficiencies and no mechanical losses. Under these conditions, if

ρ air A T ρ water A P > 1 2 , \frac{\rho_{\text{air}} A_T }{\rho_{\text{water}} A_P} > \frac{1}{2}, ρwaterAPρairAT>21,the net force will be positive and the boat will move forward. Since ρ air ρ water ≈ 1 1000 \frac{\rho_{\text{air}}}{\rho_{\text{water}}} \approx \frac{1}{1000} ρwaterρair≈10001 then

A T > 500 A P A_T > 500 A_P AT>500APor, the ratio of the wind turbine diameter to the propeller diameter needs to be more than 22.4 22.4 22.4.

Faster than the Wind in Any Direction¶

Downwind¶

Mark Drela is Director of the Wright Brothers Wind Tunnel and a professor in the AeroAstro department at MIT. His interest in the push-me-pull-you concept led him to write "Dead-Downwind Faster Than The Wind (DDWFTTW) Analysis." Assume the boat is in motion and the boat velocity is greater than the wind velocity.

Power is force times velocity, P = F v P = Fv P=Fv, but there will be some loss due to inefficiencies. For the water propeller

P W = F P V η P (1) P_W = F_P V \eta_P \tag{1} PW=FPVηP(1)and for the air turbine

P A η A = F A ( V − W ) (2) P_A \eta_A = F_A (V-W) \tag{2} PAηA=FA(V−W)(2)which can be rewritten as

P A = 1 η A F A ( V − W ) . P_A = \frac{1}{\eta_A} F_A (V-W). PA=ηA1FA(V−W).The efficiency factors η P \eta_P ηP and η A \eta_A ηA appear on opposite sides of the equal sign in these two equations because power is being taken from the water with efficiency η P \eta_P ηP, while the wind turbine puts power into the air with efficiency η A \eta_A ηA.

The apparent wind velocity at the air turbine is the difference between the boat velocity V V V and the true wind speed W W W. Although the transmission gear efficiency is usually quite high, some loss will occur, so the power at the air turbine will be less than the power at the propeller,

P A = P W η G . (3) P_A = P_W \eta_G. \tag{3} PA=PWηG.(3)Substituting ( 1 ) (1) (1) and ( 2 ) (2) (2) into ( 3 ) (3) (3),

F A ( V − W ) η A = F P V η P η G F A = F P V V − W η P η G η A . \begin{aligned} \frac{F_A (V-W)}{\eta_A} &= F_P V \eta_P \eta_G \\ F_A &= F_P \frac{V}{V-W} \eta_P \eta_G \eta_A. \\ \end{aligned} ηAFA(V−W)FA=FPVηPηG=FPV−WVηPηGηA.The available force to push the boat downwind is the difference between the force generated by water on the propeller and the force generated by the air turbine,

F net = F A − F W = ( F P V V − W η P η G η A ) − ( F P V η P η G ) = F P ( V V − W η P η G η A − 1 ) . \begin{aligned} F_{\text{net}} &= F_A - F_W = \left( F_P \frac{V}{V-W} \eta_P \eta_G \eta_A \right) - \left( F_P V \eta_P \eta_G \right) \\ &= F_P \left( \frac{V}{V-W} \eta_P \eta_G \eta_A - 1 \right). \end{aligned} Fnet=FA−FW=(FPV−WVηPηGηA)−(FPVηPηG)=FP(V−WVηPηGηA−1).For the net force on the boat to be positive, this condition has to be true:

V V − W η P η G η A > 1. \frac{V}{V-W} \eta_P \eta_G \eta_A > 1. V−WVηPηGηA>1.Upwind¶

Reversing the wind direction, the same analysis is possible, but the apparent wind velocity at the air turbine is W + V W+V W+V. The power extracted by the air turbine becomes

P A = F A ( V + W ) η A P_A = F_A (V+W) \eta_A \\ PA=FA(V+W)ηAand the power provided by the propeller is

P W η P = F P V P W = F P V η P . \begin{aligned} P_W \eta_P &= F_P V \\ P_W &= \frac{F_P V}{\eta_P}. \end{aligned} PWηPPW=FPV=ηPFPV.The gearing results in power loss from the air turbine to the propeller,

P W = P A η G , P_W = P_A \eta_G, PW=PAηG,so

F P V = F A ( V + W ) η A η G η P F P = F A V + W V η A η G η P \begin{aligned} F_P V &= F_A (V+W) \eta_A \eta_G \eta_P \\ F_P &= F_A \frac{V+W}{V} \eta_A \eta_G \eta_P \end{aligned} FPVFP=FA(V+W)ηAηGηP=FAVV+WηAηGηPThe net force is the force of the propeller minus the force on the turbine,

F net = F P − F A = F A ( V + W V η A η G η P − 1 ) . F_{\text{net}} = F_P - F_A = F_A \left( \frac{V+W}{V} \eta_A \eta_G \eta_P - 1 \right). Fnet=FP−FA=FA(VV+WηAηGηP−1).As in the downwind case, if

V + W V η A η G η P > 1 \frac{V+W}{V} \eta_A \eta_G \eta_P > 1 VV+WηAηGηP>1then the boat will move directly into the wind.

Enough With All of the Physics Equations!¶

Is there a more intuitive way to understand how a boat can go downwind faster than the wind using an air turbine connected to a propeller? The Greenbird is a wind-powered land vehicle equipped with a wing sail able to reach 126.2 mph. The physics are the same as described for iceboats above, but by carefully minimizing drag and maximizing the power derived from the wing, the team set the world land speed record.

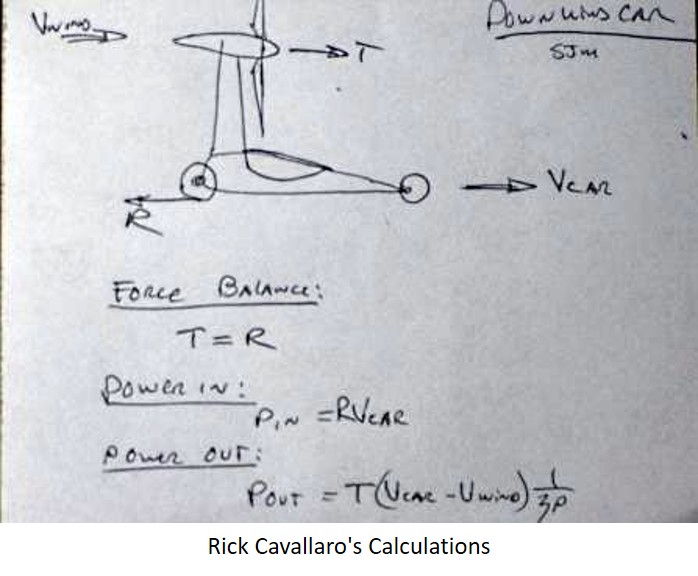

Rick Cavallaro and his team built the Blackbird achieving downwind speeds three times the wind speed, using a turbine geared to the wheels. When the vehicle begins moving downwind, the wheels turn which drives the turbine. The air at the turbine moves backward relative to the position of the cart causing it to accelerate. This makes the wheels turn faster, turning the turbine blades faster. The key is to understand this from the point of view of the person sitting in the cart. To the driver, the wheels spin due to the forward motion of the vehicle, while the turbine blows the air backwards relative to the vehicle.

Rick gave a talk to the St. Francis Yacht Club on January 18, 2017, in which he gives multiple explanations about why the physics works. In the talk, he says he's found that no single explanation seems to satisfy everyone, so he gives several ways to think about it and hopes that one will work for you. Another explanation was provided by particlezoo on the Physics Forums, but seeing is believing, so check out Derek Muller's Veritasium channel, "Risking My Life To Settle A Physics Debate".

Even after building the Blackbird and having the North American Land Sailing Association certify it went 2.8 times the speed of the wind downwind, not everyone was convinced. Rick wrote an article for Wired Magazine in 2010 called "A Long, Strange Trip Downwind Faster Than the Wind" where he describes the reaction from aerodynamicists and physicists detailing all of the violations of the Laws of Thermodynamics, and the impossibility of such a vehicle. A friend told him, “Someday one of these will hang from the rafters of the Air and Space Museum with a plaque which will read, ‘In the early part of the century, this device caused physics and aero professors everywhere to storm out of their classrooms in absolute frustration.’”

Image credits¶

Hero: A tribute to the pushmi-pullyu Jeva Lange, Jan 16, 2020. From Doctor Dolittle, 1967.

OBEY: Shepard Fairey, Pinterest

Push-me-pull-you Boat: Designed by Peter Kauffman and Eric Lindahl, Scientific American, Dec. 1975, C.L. Stong, Amateur Scientist, pg. 124

Rick Cavallaro's Blackbird: A YouTuber bet a physicist $10,000 that a wind-powered vehicle could travel twice as fast as the wind itself — and won. Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, Jul 28, 2021.

Rick Cavallaro's Calculations: A Long, Strange Trip Downwind Faster Than the Wind. Rick Cavallaro, Wired, Aug 27, 2018.

References¶

- Dead-Downwind Faster Than The Wind (DDWFTTW) Analysis. Mark Drela, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- A Long, Strange Trip Downwind Faster Than the Wind. Rick Cavallaro, Wired, Aug 27, 2018.

- A YouTuber Bet a Physicist $10,000 That a Wind-Powered Vehicle Could Travel Twice as Fast as the Wind Itself — and Won. Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, Jul 28, 2021.

- The Physics of a Push-Me Pull-You Boat. B. L. Blackford, American Journal of Physics, 1978.

- Risking My Life to Settle a Physics Debate. Derek Muller, Veritasium, YouTube, Jun 2021.

- Wind Turbine Power: The Betz Limit and Beyond. Mahmoud Huleihil, Gedalya Mazor.

- Greenbird - The Wind-Powered Land Speed Record. Wikipedia, retrieved Mar 2025.

- Pushmi-Pullyu - A Tribute to the Fictional Creature. Jeva Lange, Yahoo News, Jan 16, 2020.

📬 Subscribe and stay in the loop. · Email · GitHub · Forum · Facebook

© 2020 – 2025 Jan De Wilde & John Peach